People that pursue preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M) with in vitro fertilization (IVF) usually do so to avoid passing down a genetic risk to their biological children. They typically do this by choosing not to transfer embryos found to carry or test “positive” for the gene change (mutation) associated with a monogenic (single-gene) disorder. It may be surprising to learn that some individuals choose to transfer embryos that are positive for the gene mutation in question. Medical professionals from ORM Fertility and NYU Langone Fertility Center, two large fertility clinics, published a 2019 article in the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics describing the experience of 17 patients that made this decision.

Background

Historically, PGT-M was done for monogenic disorders with well-described or severe medical symptoms that began in infancy or childhood. PGT-M use has increased over the past 20 years, and it is now expanding to include monogenic disorders with milder symptoms, variable symptoms, or those that may not begin until adulthood. A 2018 opinion from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Ethics Committee stated that PGT-M for adult-onset disorders is “ethically justifiable” in certain circumstances. The opinion document offered medical professionals guidance by describing specific elements to consider if/when PGT-M is being requested for adult-onset disorders.

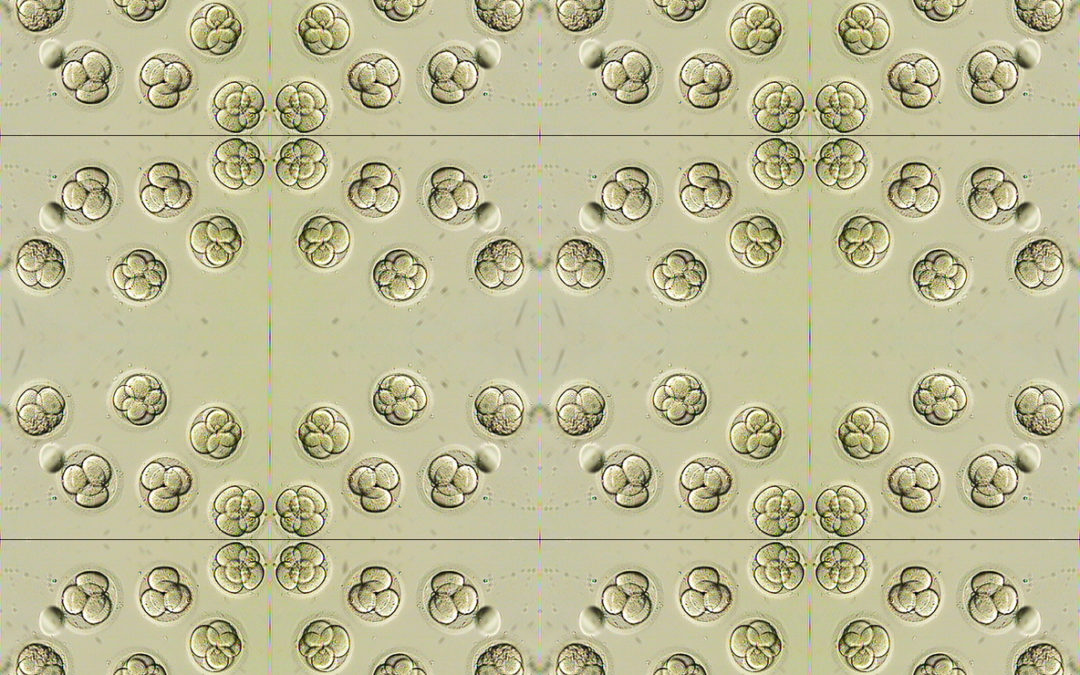

IVF/PGT-M cycles often may not result in embryos that are “unaffected” for the disorder in question. Particularly if a patient has PGT for aneuploidy (PGT-A) before having PGT-M, this may further reduce the embryo yield of “normal” embryos due to the high rate of chromosome abnormalities. If no embryos with negative genetic test results are available for transfer, some individuals choose to transfer embryos with positive genetic test results instead. As Andria Besser, genetic counselor and lead author of the 2019 paper offered, “The vast majority of patients don’t go into the PGT process with plans to transfer embryos with positive results; usually it’s only considered as a last resort.”

Study Participants

The authors did a retrospective review of patient charts prior to May 2019. Between both centers, the 17 included patients had frozen embryo transfers following embryo biopsy (blastomere or trophoectoderm) and PGT-M. These patients chose to transfer embryos with positive PGT-M results for a monogenic disorder that would usually cause symptoms for an individual at some point. Embryos that carried a single mutation for an autosomal recessive disorder were not included because these individuals do not usually develop symptoms.

Results

The 17 patients described in the article chose to transfer 23 embryos. As a group, these embryos tested positive for 9 different monogenic disorders, with varying inheritance patterns.

Most often, patients chose to transfer an embryo that tested positive for hereditary cancer risk. Of these, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome was the most common disorder and all of the transferred embryos in this group were male.

About 61% (14/23) of all transferred embryos tested positive for a disorder that causes symptoms that usually begin in adulthood, not childhood. About 70% (16/23) of all embryos tested positive for a disorder that does not always cause symptoms when a gene mutation is present (reduced penetrance). About 96% (22/23) of the embryos tested positive for a disorder with available medical management or treatment.

Conclusions

Most patients pursuing PGT-M still embark on this process to remove or reduce a child’s risk for a genetic disorder. But this study found that, particularly if they have no option to transfer an embryo without the associated gene mutation, many patients are open to transferring an embryo that has the gene mutation. “This is not an easy decision for patients,” says Emily Mounts, genetic counselor, and co-author. “They do not make this decision lightly… but so far the requests we have received have been very thoughtful,” she continued.

The authors describe many factors that go into this decision, such as a patient’s ability (financially or otherwise) to have future opportunities for IVF with PGT. For some, this may be their only chance to have IVF and PGT. Other factors include the expected severity of symptoms with a disorder when symptoms might occur in a person’s life if an embryo’s biological sex impacts symptoms (such as a female’s breast cancer risk versus a male’s breast cancer risk), and if treatments are available or on the horizon. Individuals who have a monogenic disorder themselves might choose to transfer an embryo with positive results because they feel more informed to support a child with the same condition.

The article also explores perspectives from healthcare providers. Maintaining a patient’s autonomy throughout the process was mentioned multiple times. As Besser said, “As long as a patient or couple has an understanding of the situation at hand, I think it’s important that they have the autonomy to make choices that are best for their family.” The study described needing to strike a careful balance between achieving patient autonomy, the intent of “doing good,” avoiding doing harm, and maintaining justice.

Clinicians follow medical guidelines and often make case-by-case decisions with their patients about transferring an embryo with a gene mutation if no guidelines exist. “Every situation deserves its own exploration of the unique aspects of that case. I think we’ve considered these in the best way possible, by involving an interdisciplinary team and being sure the patient has been counseled adequately,” offered Mounts. Both Mounts and Besser also said they now make sure to discuss the possibility of transferring embryos with positive results when providing genetic counseling to their patients.

Limitations

The number of patients included in the study was small. Also, patients were not contacted to get their direct thoughts and opinions about their experiences and the decisions they made.

Final Thoughts

This article offers insights about a growing issue for patients and healthcare providers involved with PGT, and one that has not been discussed much to date. It offers a framework for future conversations needed to best support a growing number of patients making important decisions about the embryos they are comfortable using to pursue a pregnancy.

Deepti is an independent consultant for Sharing Healthy Genes. She is a highly skilled writer and editor with medical communications and marketing experience, which blends with her 20+ years of clinical acumen as a certified genetic counselor in the U.S. and Canada. Deepti has an active consulting business and is an engaged member of the National Society of Genetic Counselors, most recently serving as a 2018-2020 Director at Large. In her downtime, you’ll find Deepti poring over cookbooks, facing down superhero quizzes from her sons, or writing about her family’s foodie gene on her blog.